Tuesday 6 August 2019

Brethren of the Coast

Chicory_Flexine

|

http://www.chicoryflexine.wales a research project by Roger Lougher and Anne-Mie Melis Unit(e) g39 2017 |

Tuesday 31 October 2017

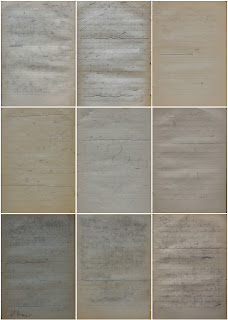

Three Flanders Landscapes | Tri Thirwedd Fflandrys a/and Three Welsh Landscapes | Tri Thirwedd Cymru

These altered photographs were inspired by the diary of Corporal John S. Lloyd, an engineer in the British Expeditionary Force. He wrote the diary whilst serving in Flanders, hence the titles, Tri Thirwedd Fflandrys, Tri Thirwedd Cymru.

The diary was first shown to Roger Lougher by Iwan Llwyd after discussions of Llwyd’s play Mae gynnon ni hawl ar y sêr. Llwyd hoped Lougher might find it inspiring. This process has been a slow one and sadly Iwan Llwyd died before he saw the results.

Lougher began photographing the diary over the period of a day. The changing light gave different colours to the paper as the light temperature changed. The words of the diary were then erased from the photographs digitally. Occasionally the artist would leave words or phrases he felt significant. The decision as to which words should be considered significant was as fickle as the changes in light. In these prints the artist has left the names of Welsh towns in Tri Thirwedd Fflandrys, and towns in Flanders in Tri Thirwedd Cymru, (The title, Tri Thirwedd Cymru, refers to the way Lloyd’s letters would have brought the war into the imagination of friends and family at home in Wales, as conversely letters recieved took Wales into Flanders.

|

| Blackwood #4 |

|

| Blackwood (close-up) |

|

| Nantgarw #5 |

|

| Ynysbwl #6 |

|

| Heuringen #7 |

|

| St. Omers #8 |

|

| Wizernes #9 |

In the face of the horror of the First World War Lougher has chosen a quiet response, one in which the marks left on the page create a blasted landscape; the paper of the page stretched and warped by the act of writing and subsequently of being read.

The first iteration of ideas inspired by John Lloyd's diary happened during Lougher's residency at Galeri, Caernerfon 2014. Different versions of Tri Thirwedd Fflandrys were exhibited at the Lle Celf, Eisteddfod Genedlaethol Llanelli, 2014

annwfn / unterritory (tirwedd #5 ymlaen / landscape #5)

Roger Lougher will use the gallery space to make an installation which in it’s last manifestation on March 14th will then be on show until March 28th.

‘Going to the usual place’ could well be the title for Roger Lougher’s residency, except his work is never what is expected. His art work is an attempt to empathetically retell the experience of his ‘usual’ work felling trees and growing plants in the ‘usual’ place, Drefelin, Carmarthenshire. The re-telling is not a verbal experience but the physical re-enacting of his work activities on trees, logs and branches he has felled and brashed; re-imaging the landscape from which the material has been drawn. This landscape is not only the physical one in which he works, but the internal landscape of memories of work held in his body, fused with musings that arise as he works. Here an obsessive worrying of Cpl. Lloyd’s diary. In this way his physical labour becomes a studio in which the artwork is sketched, rehearsed and practiced. ‘A Feeling of What Happens” ,as the neurologist Antonio De Massio might say, is the outcome.

The installation in the gallery is a tangential response to the atmosphere of the diary and a celebration of the quiet routines with which we fill our days; it foregrounds the banal routine that is the greater part of warfare rather than the violent drama of conflict. This is Lougher “doing the usual” working with familiar materials and contemplating ideas about landscape, work and warfare.

In the cafe Lougher has installed table-talkers. These contain a photograph of egg and chips and a diary page from which all the words have been erased apart from “had the usual”, “went to the usual place”, etc. The “usual place” in Flanders were the informal cafés - estaminets - that flourished providing egg and chips to the troops behind the lines and also other more intimate and problematic encounters when they housed brothels.

Lougher’s understanding of Annwfn needs explaining. He has a sense that we live in a layered world and if any of these layers delaminate we can suddenly find ourselves in a visually familiar place but one seemingly utterly changed and foreign in it’s feeling. An epiphany held in time by the gallery space.

Tuesday 15 August 2017

Y Gwir yn Erbyn y Byd

I have become interested in the non-human world and how this can inform the way I see landscape. This is a way of collapsing the polarity of country and city and seeing the world as a continuum of experience. It is also a way of imagining other worlds that are inclusive of all life.

The video was captured by penny d. jones. The performance was a live affair and penny kindly videoed the event as a record rather than the video being an artwork. The music is by Andrew Strong and is an arrangement of a traditional Morris tune Ilbury Hill.

Reading List

Anne Rainsbury, Curator Chepstow Museum:

John Barrell, "The Dark Side of the Landscape: The Rural Poor in English Painting 1730-1840" (Cambridge University Press, 1980)

Ann Bermingham "Landscape and Ideology: The English Rustic Tradition, 1740-1860" (University of California Press, 1986)

Stephen Copley and Peter Garside editors "The Politics of the Picturesque" (Cambridge University Press1994/2010)

Something I found in Cardiff Library

MS 3.337 John Byng - Tour of South Wales (1787)

Dr. Madeleine Gray

Richard Warner, A Walk Through Wales in 1797

E. D. Clarke, A tour through the south of England, Wales, and part of Ireland Made during the Summer of 1791

Malcom Andrews, The Search for the Picturesque: Landscape Aesthetics and Tourism in Britain, 1760-1800

Residency at Tintern 2016

Thematic approaches could involve:

• an exploration of the history of heritage at Tintern Abbey that focuses on the original medieval ruins and Cistercian history

• a philosophical examination of how antiquarians viewed the past or how we view the past in the twenty-first century

• an exploration of the theme of ‘time, people and place’. (Cadw/Arts Coucil Wales 2015)

As you will have seen, if you read through the posts above, Tintern Abbey was occupied by the Cistercian monks for four hundred years. In taking the Abbey archeology back to this period all the subsequent history has been removed and little reference is made to the continuous habitation of the site over the time since its dissolution in 1536. In the 1970s the last dwelling within the site was purchased, demolished and erased.

My interest in the site was first piqued when I read Gilpin's book about his trip down the River Wye (see subsequent posts) where he describes people living in the ruins and acting as unofficial tour guides. I talked with the Anne Rainsbury, curator of Chepstow Museum, who very kindly gave me a reading list and suggested other people I might like to contact. From talking to Dr. Madeleine Gray and Dr. David R.Howell (here they are looking at one of the gravestones within the abbey church)

I learnt that of the contiuous habitation of Tintern Abbey.

It seems likely that the Picturesque visitors (including Gilpin) who came in the eighteenth century exaggerated the poverty of the people living in the abbey since this increased the picturesque frisson of meeting them. The visitors assessment of the poverty of the inhabitants of Tintern might also reflect the class outlook of the visitors. Whilst this is the beginning of modern tourism this was not mass tourism but the leisure activity of the leisured classes. This does not mean that there were no beggars. It is possible that people who had maybe migrated there for work were unable to claim relief from the parish as Tintern would not have been the parish they were born in and so amongst the cottagers there may have been some who were destitute through age or industrial injury.

The first person to live there was the mother of Henry Somerset, Earl of Worcester until she moved to properties in the south of England. Once she left the buildings were rented out to people who lived and worked in the area, in the charcoal burning, lime kilns, iron works and brass foundry (established 1538 within the walls of the abbey). Stone was quarried from the site to build these factories and further cottages.

It's perhaps clear that I was less interested in the Cistercian History. This needs little explication since it is so obvious on the site, although perhaps the political implications are less obvious. The Cistercian monks lived in a world where they were separated by class, language and geneology from those surrounding them. All the work was done by the lay-brothers who were local gentry and peasants. They wouldn't have eaten together or talked or had commerce. Their purpose, beyond their religious vocation was to extend the power of the Norman overlord at Chepstow (William fitzOsbern and later William Marshal and Richard de Clare).

• an exploration of the history of heritage at Tintern Abbey that focuses on the original medieval ruins and Cistercian history

• a philosophical examination of how antiquarians viewed the past or how we view the past in the twenty-first century

• an exploration of the theme of ‘time, people and place’. (Cadw/Arts Coucil Wales 2015)

As you will have seen, if you read through the posts above, Tintern Abbey was occupied by the Cistercian monks for four hundred years. In taking the Abbey archeology back to this period all the subsequent history has been removed and little reference is made to the continuous habitation of the site over the time since its dissolution in 1536. In the 1970s the last dwelling within the site was purchased, demolished and erased.

My interest in the site was first piqued when I read Gilpin's book about his trip down the River Wye (see subsequent posts) where he describes people living in the ruins and acting as unofficial tour guides. I talked with the Anne Rainsbury, curator of Chepstow Museum, who very kindly gave me a reading list and suggested other people I might like to contact. From talking to Dr. Madeleine Gray and Dr. David R.Howell (here they are looking at one of the gravestones within the abbey church)

I learnt that of the contiuous habitation of Tintern Abbey.

It seems likely that the Picturesque visitors (including Gilpin) who came in the eighteenth century exaggerated the poverty of the people living in the abbey since this increased the picturesque frisson of meeting them. The visitors assessment of the poverty of the inhabitants of Tintern might also reflect the class outlook of the visitors. Whilst this is the beginning of modern tourism this was not mass tourism but the leisure activity of the leisured classes. This does not mean that there were no beggars. It is possible that people who had maybe migrated there for work were unable to claim relief from the parish as Tintern would not have been the parish they were born in and so amongst the cottagers there may have been some who were destitute through age or industrial injury.

The first person to live there was the mother of Henry Somerset, Earl of Worcester until she moved to properties in the south of England. Once she left the buildings were rented out to people who lived and worked in the area, in the charcoal burning, lime kilns, iron works and brass foundry (established 1538 within the walls of the abbey). Stone was quarried from the site to build these factories and further cottages.

It's perhaps clear that I was less interested in the Cistercian History. This needs little explication since it is so obvious on the site, although perhaps the political implications are less obvious. The Cistercian monks lived in a world where they were separated by class, language and geneology from those surrounding them. All the work was done by the lay-brothers who were local gentry and peasants. They wouldn't have eaten together or talked or had commerce. Their purpose, beyond their religious vocation was to extend the power of the Norman overlord at Chepstow (William fitzOsbern and later William Marshal and Richard de Clare).

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)